No other adult performer has achieved the name recognition enjoyed by John Holmes in his lifetime, yet Dawn Schiller’s fascinating new memoir “The Road Through Wonderland: Surviving John Holmes

No other adult performer has achieved the name recognition enjoyed by John Holmes in his lifetime, yet Dawn Schiller’s fascinating new memoir “The Road Through Wonderland: Surviving John Holmes” takes place almost entirely outside the industry that made him famous.

Stripped of Holmes’ goofy but iconic porn storyline (and containing only one mention of his penis), “Wonderland”‘s linear progression, from Holmes as Schiller’s father figure to Holmes as her boyfriend to Holmes as a violent drug addict, thief, and pimp, becomes less a story about John Holmes than it is about the horrors of cocaine addiction and the phenomenon of “throwaway teens.”

“If it hadn’t been John Holmes,” Schiller told me, “it would have been someone else.”

In the summer of 1976, when she was 15, Schiller washed up in the L.A. suburb of Glendale, a throwaway teen before that term was invented. She and her sister had agreed to an uncertain future with their divorced father, Wayne, and had traveled from their home in Florida to a tidy courtyard of bungalows managed by a strange couple named John and Sharon Holmes.

The first half of “TRTW” reads like a combination of “The Grapes of Wrath” and “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.” Schiller’s family moves according to the caprices of their charming but irresponsible father and is often left hungry and impoverished, waiting for him to return from mysterious jobs overseas. So when there is food on the table or when some stability arrives, the reader is vicariously relieved.

And things change for the better—at least for a while—when the sisters arrive in Glendale with their father, who soon makes plans to leave them again. John Holmes gives the undernourished girls gardening work, and begins taking them on day trips.

Though few people in the porn world knew it, Holmes had been married since the mid-60’s.

The Holmes couple had an unorthodox relationship (“like brother and sister” as it was explained to Schiller) and John, then 32, made a point of taking care of Schiller and her sister. Compared with her life up to that point, it was an idyllic time.

It isn’t for a while that Schiller learns Holmes’ other occupation. She is apprehensive, but if she’s jealous she doesn’t let on; Schiller’s relationship with him up to that point is as a kid sister with benefits; Holmes keeps the courtyard tenants supplied with pot from his ever-present briefcase and, after a while, when both her father and sister leave, Dawn moves into an apartment of her own on the property and then goes to live with John and Sharon in their bungalow.

Sharon, “an old-school nurse,” encourages Dawn to get her Licensed Practical Nurse certificate. The makeshift family plays board games, eats dinner and watches television together. Schiller and John become very close. He even takes her to a nude beach.

Shortly before her 16th birthday, Dawn and John have sex for the first time.

“I was looking at it through the lens of a child,” Schiller told me. “I should have seen there were red flags from the beginning.”

Among the red flags were John’s possessiveness and childishness that often accompanied his need to create the family he lacked.

“We’d all be playing some game,” Schiller says, “and if he wasn’t winning, he’d knock over the table and throw the pieces on the floor.”

And Holmes, Schiller says, would interrogate her about classmates and would alienate visiting family members, trying to keep a wall around her. It was rare in their early lives together that Holmes would give her a glimpse of his porn life; she was startled at his fame when he took her to a screening of “The Autobiography of a Flea” and he drew a crowd of autograph seekers outside the theatre.

“I probably should have had more stable people in my life,” Schiller told me. “But I didn’t know anyone else. My world had always been very small.”

As a first-person narrative, “TRTW” accomplishes a sense of inevitability. As we travel with Schiller from her birth in New Jersey through the first of her father’s long absences during the Vietnam War, then through the family’s decline as it moves to bleak and dangerous Carol City, Florida, we see Schiller growing up fatherless with a strict and jealous mother from Germany, who is doing her best but is little more than a child herself.

Schiller meets John Holmes, himself the product of a broken and abusive home (although Holmes’ childhood in Ohio is not covered in this book), and falls in love with him.

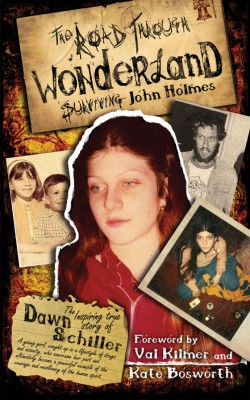

In the past several years a growing body of Holmesiana has appeared, from Cass Paley’s and Rodger Jacobs’ documentary “Wadd” to Alex Winter’s movie “Wonderland” (starring Val Kilmer as Holmes and Kate Bosworth as Schiller, both of whom Schiller thanks in her book) to the excellent oral history “John Holmes: A Life Measured in Inches” by Jill Nelson and Jennifer Sugar. I also hear that there are books in the works from several other people close to Holmes.

What we learn from the collected documentation on Holmes (especially “Wadd” and “Inches”) is that Holmes led many lives that he tried to keep separate, that of the porn star, the family man, the police informant, and the drug addict. This is why reading Schiller’s memoir alone might leave the reader wondering how none of these different worlds collided.

But cocaine, as always, helped break down those barriers.

When Holmes graduates from pot to cocaine in the late 70’s, everything changes. The last half of Schiller’s memoir is a decline far more nightmarish than her early teen years in Carol City, as Holmes steals from family and friends, gets Schiller addicted to freebase cocaine, beats her, and pimps her for drug money.

Schiller’s skill as a writer is evident in both her narrative pacing and the small glimpses of her life in and out of distress. One vivid anecdote describes an evening when Schiller opens her motel door to find Frosty, a strung out streetwalker who begs for Schiller’s help finding a vein.

Scared that Holmes will beat her if she leaves the room, Schiller nevertheless goes across the hall to Frosty’s bathroom, where the two can’t find a vein anywhere, until Frosty takes off her bra. Squeezing Frosty’s breast, Schiller watches in horror as she injects into a nipple.

It is tempting now and then to wonder, during “TRTW,” how a scrappy girl like Schiller allowed things to get so bad. We believe both Holmes’ magnetism and manipulation, we understand the personality changes of drug addiction, and we know that Schiller didn’t have a good male role model, but every fatherless girl doesn’t end up a drug-addicted prostitute. At times it seems that Schiller avoids taking responsibility and paints herself as powerless to resist Holmes’ infantile charms and violence.

She makes two escape attempts before the third one finally takes. The first results in her being kidnapped by a man who may have been one of L.A.’s infamous “Hillside Stranglers” and the second finds her fleeing from a position of drug-indentured prostitution to her mother in Oregon (in a moment that in any other memoir would be horrific but in this one is almost humorous, Schiller is helped in her second attempt by a kindly senior citizen who just wants to touch her butt), only to be sweet-talked back.

It is the fact that she actually made it out of Holmes physical clutches and ran a thousand miles, reunited with her mother and siblings, and even got a job that is testament to Holmes’ persuasiveness. Tracking down her number and calling her every day, Holmes charmed her mother, apologized, said he was clean, and talked Schiller back onto a plane.

He picks her up at the Burbank Airport and Schiller is crestfallen to see him steal some luggage off the carousel.

On the afternoon of July 1, 1981, Holmes returns to the cheap hotel room he and Schiller share, agitated beyond his normal coke crashes. He screams in his sleep. He had either been witness to or a participant in a quadruple homicide known as the Wonderland Murders, which he almost certainly helped facilitate.

“Those people on Wonderland Avenue are dead because of one of John’s bright ideas,” Schiller told me.

Shortly after the murders, Holmes is arrested and jailed by the LAPD. He must somehow exonerate himself with the cops while staying in the good graces of vicious drug kingpin Eddie Nash. And he almost gets away with it.

“Even the psychiatrist in jail fell in love with him,” says Schiller ruefully. “He was very charming.”

It only gets worse; to prove his loyalty to the man paying him in drugs, Schiller reports that Holmes pimped her out to Eddie Nash, too.

But then the two of them leave Los Angeles, traveling across the country to Miami, where they both find odd jobs. And for a brief moment hope returns, even though Holmes is still breaking into cars and attempting to conceal his drug use.

Finally, one night in Miami in late 1981, after he has whored her out on the beach, Schiller leaves Holmes for the third and final time and never sees him again. He dies of AIDS in Los Angeles in 1988.

Holmes may have had a shot at redemption had he lived, Schiller told me, but it wasn’t likely.

“His social immaturity and his ego were his worst enemies,” Schiller says. “And he was bound and crippled by bad decisions. Redemption is a lot of work, but people have done it. I’m not sure he was capable of it, though.”

Memoirs are tricky things; they are like hearing one side of an argument and are almost always convincing. But anyone familiar with some of the other published or filmed material on Holmes will find inconsistencies in both Schiller’s timeline and tone.

Schiller dismisses much of this as bias or the wishful thinking of people who want Holmes to stand in for the porn world in general.

“Porn is not a part of my world. Even John, when he would talk about it, would say that he hated ‘those people,'” Schiller told me. “I have questions about people who consider him a hero, but then, he was a self-centered chameleon and was very charming.”

Indeed, few people saw all sides of John Holmes. Glendale is just a few minutes away from Porn Valley, but it represents a massive ideological divide. Not only that, but also by all accounts Holmes off coke was much different from Holmes the cokehead. Add to that Holmes’ own secrecy about his many lives and it is understandable that different people give varying accounts of him.

Something that may hurt Schiller’s credibility is the liberal amount of speaking she does for Sharon Holmes, who is now ill and under legal guardianship. Schiller reveals never-before-published stories of Sharon’s adventures following the Wonderland murders that would strain credulity if we weren’t aware of how fucked up things were already. But it is that Schiller speaks for Sharon, even revealing that the older woman swore her to secrecy, that seems odd.

In addition, there are a few other revelations that, were it not for the well-ordered timeline that otherwise makes this an excellent memoir, seem too convenient. Early in the book Schiller describes rolling joints for her father in Florida. Much later, when Holmes starts using cocaine, she reveals that she did cocaine with her father back then, too. At the very least, including her early coke use chronologically would serve as foreshadowing.

Similarly, it is only after her first intercourse with Holmes that she reveals that she lost her virginity back in Florida. We know the book isn’t about porn, but if Schiller is going to use Holmes’ name to publicize the plight of throwaway teens, it would have been polite to not lead us to think for hundreds of pages that she was going to lose her virginity to the most famous porn star of all time.

And that is why memoirs are tricky; they are the artful representations of a changing mind. Schiller has said things to other interviewers that contradict the tone, if not the letter, of some of “The Road through Wonderland.”

But these things do not significantly take away from the power of this book or its message. In fact, we can see the same things happen today as teens become more anonymous and less parented.

Schiller lives in Oregon, is a regular lecturer for the National Center for Victims of Crime, and is collaborating on a forthcoming Young Adult book about throwaway teens. She claims 12 years of sobriety.

“There’s so much more after you’re out of that life,” she says.

Previously on Porn Valley Observed: John Holmes book also measured in inches; The Wonderland Murders

This is a balanced review of Schiller’s expressive and at times, mystifying memoir. On the plus side, in conjunction with the book serving as a welcome voice for “throw-away teens,” TRTW functions powerfully as an anti-drug vehicle. Dawn’s story is a testimony to the fact that freebase/chemical addiction radically alters human behavior. It causes one to ponder if Holmes had not become violent toward Schiller while under the influence of chemicals, would she have stayed with him despite the inappropriate and unconventional nature of their relationship? The reader gets a sense (at least in the first half of the book) that Dawn felt a kind of genuine love for Holmes, as she has expressed in past interviews. One also speculates if it had been offered in 1980/’81 when Holmes would was rapidly spiraling downward – would he have eventually sought help for his addictive condition? Unfortunately, recovery and support programs weren’t readily available for drug addicts during the latter part of the 1970s and early 1980s.

TRTW is very readable and engrossing in parts, but portions of the narrative leaves the reader questioning certain elements. As is intimated in your review, many children experience parental neglect, emotional abandonment and various levels of family dysfunction (that seemed to punctuate the ’70s generation), but somewhere along the line, taking some ownership of our actions becomes part of the maturity process. Also significant (while on the subject of “throw-away teens”) is the fact that Holmes experienced disturbing episodes of abuse at the hands of two step-fathers – it would have made for an enlightening sidebar if Schiller had brought attention to that relevant point, considering her work with the group she founded: E.S.T.E.A.M.

Interesting is Schiller’s dismissal of TRTW’s timeline and tone contradictions (with respect to previous articles and interviews) by indicating that her critics are fans who revere Holmes’ stature in porn’s kingdom. When an individual elects to write a book that entails personal (and many ugly) details about someone who is a public figure, naturally, it will be scrutinized for holes. Particularly when that public figure has already been the subject of several other projects in which the author has participated.

Did anyone interview Tamara Longley, Melissa Melendez or Kimberly Carson? They did sex scenes with Holmes very close to the time he contacted aids. It must have been scary for them and I wonder how they feel about their close call with an infected John Holmes?

We weren’t able to interview Tamara Longley, Kimberly Carson or Melissa Melendez for our book, but we did speak with Amber Lynn Allen who had worked with Holmes (while infected) in his final two movies shot in Italy in the fall of 1986: The Devil in Mr. Holmes, and The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empress. Lynn told us that she had been angry, scared and hurt for almost twenty years that Holmes had knowingly exposed her to the virus. It wasn’t until celebrating a decade of sobriety in 2008, after her own extensive history with drug and alcohol abuse that Lynn was able to finally forgive Holmes. She said she realized “John wasn’t evil; he was an addict” and believed that years of drug abuse had compromised his ability to think rationally. Cicciolini (Ilona Staller) who had also worked with John in his last two pictures has expressed similar concerns about having been put at risk. Thankfully, there are no reported cases of anyone contracting HIV from John Holmes. Laurie Holmes (John’s widow) is also AIDS free.